CATARACT SURGERY TODAY IS INCREDIBLY DIFFERENT THAN it was 50 years ago, and it’s a shining example of a medical marvel. Technological and medical advancements have given our skilled surgeons the tools to perfect the human eye with high levels of accuracy and precision. Studies show that refractive outcomes are within 1.0D of predicted outcomes in over 90% of cataract surgeries, and 70% are within 0.5D.1,2 But even as our technology and accuracy improve, the increasing level of choice muddies the water of our textbook-perfect outcomes. Because as we say, 20/happy is a real thing, and understanding what happy means is crucial when it comes to deciding the final outcomes for our patients’ vision.

As technology has evolved, the decision tree for cataract surgery has expanded and gotten more complicated. To lay out a brief timeline of the evolution that followed monofocal and toric intraocular lens (IOL) implants:3

- 1990s: Multifocal IOLs entered the market

- 2000s: Accommodating IOLs entered the market

- 2008: Femtosecond laser was first used to assist cataract surgery

- 2017: Extended depth of focus (EDOF) IOL entered the market

- 2019: Trifocal IOL entered the market

- 2020: Commercially available light adjustable IOL entered the market

The recent exponential advancement in technology is incredible for providing the best outcome for our patients, but also creates significantly more variables to sift through when deciding on what the best option will be for each patient.

So how do we decide between best correcting for distance vision vs. monovision vs. multifocal? Leave it to the patient? Utilize a patient survey? Trust the surgeon’s first impression? Leave it to the longstanding optometrist’s recommendation? In the end it typically is a combination of these options, but let’s discuss ways to figure out what type of patient is best for different types of intraocular lens implants.

There are no firm rules on the best way to do this, but one option regularly implemented is mimicking potential outcomes with contact lens demonstrations. Similar concepts used in fitting presbyopic contact lens options can help a patient relate to the idea of the different IOL options. Plus, giving your patient the option to “try before you buy,” or test run the proposed visual outcome before they commit can help alleviate your patients’ burden of deciding their visual fate.

Paralleling the Contact Lens Fitting Process to the IOL Process

The first step is to critically assess each patient’s current refractive error, previous preferences with contact lens wear, and viewing habits. This will ultimately lead to the best outcome for your patient. Another consideration is ocular dominance and how strongly the eyes “prefer” to work together. Finally, some patients may ultimately choose to reject any presbyopic correction and opt for optimizing distance vision in both eyes. This leads to a few options varying in complexity, visual outcomes, and pricing.

The simplest option is single vision distance correction. This is the easiest considering the optics and math involved as well as the anticipated outcomes. But before a patient fully commits to this option, a good clinician should provide some additional thought-provoking questions to elicit consideration from the patient on how they will handle all intermediate and near demands.

Single vision correction can be disruptive to most people if they aren’t used to distance-only vision. Especially for presbyopic myopic patients, the new reality of needing reading glasses for all near demands must be thoroughly described to the patient as this paradigm shift is often unanticipated. For example, when a patient decides to remove the progressive design from their glasses they have always had—to save some money and because “it doesn’t really help,”—they almost always return disappointed as they realize the lack of clarity at the dashboard, on the iPad, or reading recipes. This scenario is important to consider when working with myopic patients; by the time most myopic patients need cataract surgery, most have worn a progressive for 20 years. If they opt for single vision correction, demonstrating this option with contact lenses may be the only way to really allow the expected outcome to “sink in.”

The next tried and true option with equally predictable outcomes is providing monovision correction. This form of correction optimizes the distance vision in one eye and provides plus power in the other eye to optimize intermediate or near vision. The eye receiving distance correction is often the dominant eye determined by various ocular dominance testing. The amount of additional plus power is determined by the patient’s near demands and requests, as well as what they tolerate. Many patients are extremely content with this outcome and freedom from any necessary spectacle correction.

Checking Eye Dominance

- Miles Test: This technique is tested with best corrected visual acuity in each eye. A patient extends both arms, brings both hands together to create a small opening, and views a target 6 meters away through the hole with both eyes open. Each eye is then occluded in turn and the target will no longer be seen when the dominant eye is occluded.

- Fogging Test: This technique is tested with best corrected visual acuity in each eye and behind the phoroptor. With both eyes open, the subject views an open letter chart and +1.00D is alternately placed in front of each eye. The most noticeable blur is the dominant eye. Equal blur can be a sign of poor adaptation to monovision.

Trialing contact lenses for the targeted monovision correction is a great way for a patient to test out this endpoint. While there could be anxiety around which eye to choose for the dominant eye, there are several studies that have found that ocular dominance is quite plastic following surgeries and most patients easily adapt to whatever they end up with.

For example, one study showed that 21% of patients change eye dominance after cataract surgery, often associated with improved visual acuity.4 Another study provided pseudophakic monovision with the dominant eye receiving distance correction and compared it to “crossed monovision” with the non-dominant eye receiving distance correction, and it found that both the normal and crossed monovision exhibited similar visual function and quality of life.5

Demonstrating the amount of monovision with contact lenses is a great way to understand the amount of anisometropia the patient will tolerate, with dominance and previous preference often playing into the outcome. What is not tolerated in spectacles or behind the phoropter will often surprisingly be well received in contact lenses. That being said, studies have shown that 1.00D leads to an ideal amount of distance and intermediate vision with the least induced aniseikonia.6

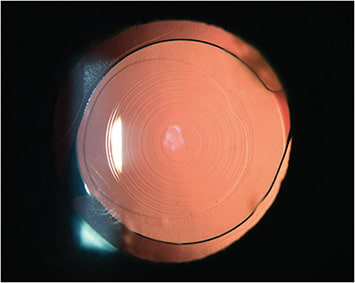

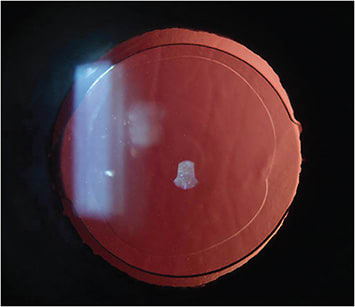

The newest and highest technological options are the rapidly improving multifocal IOLs. This can provide a range of vision in one or both eyes, often keeping distance vision the priority, but enhancing the near vision. These options historically have the highest risk of patient dissatisfaction and are often avoided with a complicated history of ocular disease (especially corneal or retinal findings). That being said, some of the newer options available—including the EDOF and trifocal IOLs—have significant success. One study found that there is a trend toward increased patient expectations of multifocal IOLs matched by excellent visual outcomes and satisfaction; 96% of patients were spectacle free at 3 months and would recommend this procedure to others.7

While we currently have multifocal contact lenses and multifocal (and trifocal, and EDOF) IOLs produced from similar manufacturers, the contacts and IOLs visual outcomes cannot be directly compared. That being said, some of the lower-powered multifocal lens options (e.g. Johnson & Johnson, Acuvue 1 Day Moist Multifocal Low) could be tried to compare to the EDOF IOLs (e.g. TECNIS Symfony IOL) due to its generally comparable add power effect. A higher-powered multifocal lens option (e.g. Alcon, Precision1 Multifocal High) could be tried to compare to the trifocal IOLs (e.g. Alcon PanOptix IOL) to mimic the larger range of focus and add power.

Regardless of your patient’s desired endpoint, here are some important thoughts to consider:

- Timing: If the first time your patient is learning about multifocal or monovision IOL options is when they have a significant cataract and are ready to sign up for cataract surgery, you likely have waited too long to do them any service in demonstrating due to a dysfunctional optical system beyond refractive error repair.

- 85% Rule: Just like with contact lenses, I like to advise the 85% rule, where the majority of the time you should be happy with your vision and the rest of the time you will likely need another tool to see your best (e.g. extended reading, crafting, driving at night).

- Trial run: For your patient that is anxious about their options, consider fitting them in contact lenses or requesting an extended wear trial of the proposed power. Advise your patients that this isn’t going to be comparing apples to apples as vision post-cataract removal will be improved and different, but at least it can be a point of reference for both the patient and the doctor to continue the conversation regarding post-operative goals.

- Build trust: Ultimately your patient needs to trust your wisdom, even with the perfect trial. Great communication, thorough testing, and a supportive team will help your patient feel comfortable with their final decision. ■

References

- Garg A, Lin JT, Latkany R, et al. Mastering the techniques of IOL power calculations. 2nd ed. New Delhi: McGraw-Hill, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2009. IOL calculation in long and short eyes.

- Hill W. IOL Power calculations: How to achieve accurate results. [Accessed 1/10/2022]. Available at: http://www.doctor-hill.com/iol-main/iol_main.htm .

- Davis G. The evolution of cataract surgery. Mo Med. 2016 Jan-Feb; 113(1): 58-62.

- Schwartz R, Yatziv Y. The effect of cataract surgery on ocular dominance. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015; 9: 2329–2333. Published online 2015 Dec 14.

- Xun Y, Wan W, Jiang L, Hu K. Crossed versus conventional pseudophakic monovision for high myopic eyes: a prospective, randomized pilot study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020 Nov 16;20(1):447.

- Naeser K, Hjortdal J, Harris W. Pseudophakic monovision: optimal distribution of refractions. Acta ophthalmol. 2014 May;92(3):270-5.

- Ison M, Scott J, Apel J, Apel A. Patient expectation, satisfaction and clinical outcomes with a new multifocal intraocular lens. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021 Oct 13:15:4131-4140.